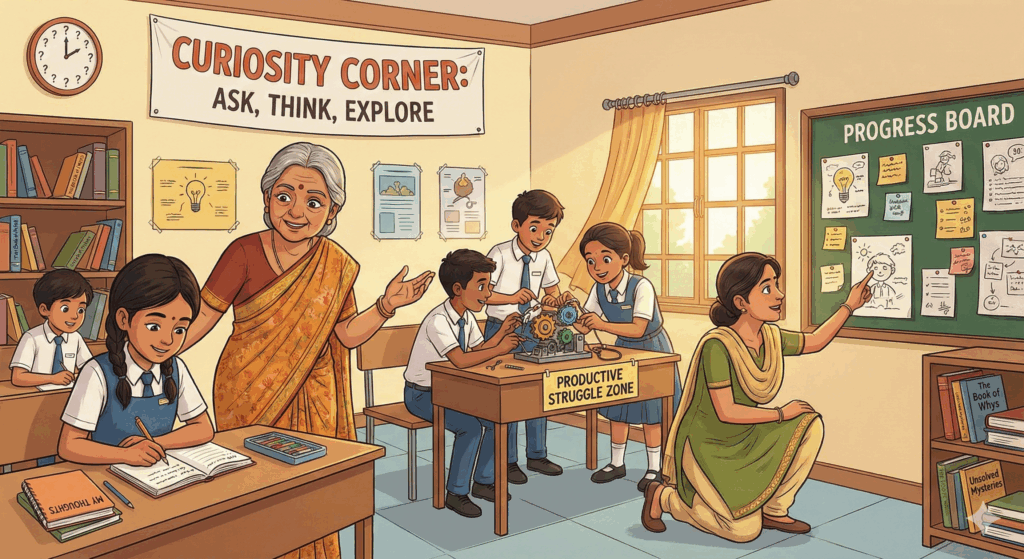

If igniting the spark is one thing, keeping the lamp burning is a whole different challenge altogether. While we have already covered how NEP 2020 calls for inquiry-based learning and play- and activity-based pedagogy in the foundational stage, it also outlines guidelines to reduce curriculum load, transform assessment, and redefine the roles of teachers. The crux of all these changes is one underlying principle: curiosity being the first step for deeper understanding. Children, therefore, should be assessed not just for the answers they give but also for the questions they ask and the thinking they demonstrate. Teachers and parents must begin to don the role of a facilitator-of curiosity and exploration, in addition to content delivery. NEP’s emphasis on holistic, multidisciplinary education aimed at developing all capacities implies that curiosity isn’t and should not be limited to science or school-but to people, ideas, and the world.

Despite adequate nurturing, curiosity could still wither. As children enter their teenage years and begin to face academic or social pressures, sustaining curiosity might become a challenge. Keeping curiosity alive requires resilience-both from elders and children.

Children in their primary grades often attend extracurricular classes aligned with their interests. But soon there is a shift in priorities with increasing academic demands. The numbers reverse in favour of the academic-oriented classes that take their place. With everything being time-bound, their curriculum, testing, and schedules, they tend to conform to a mindset of-‘Do what’s told and take what’s served.’

A couple of years ago, a popular chain of schools was in the news for claiming to prepare children for IIT-JEE from as early as kindergarten or first grade. “Was that even scientific?” one is left to wonder. Are we conditioning children for academic competition before they have even blinked twice?

An acquaintance – 14-year-old girl-so averse to classes and school, rightfully asked, ‘I want to be an art teacher when I grow up. Why don’t I get to paint now? Why am I being asked to wait until I complete my 10th or 12th grade?

On a lighter tone, how many of us are familiar with being told, ‘You should have learnt this in your earlier classes’ or ‘You will learn this higher classes’ – only to realise that we did not learn it in either!

A recent article in a national newspaper brought to the fore an important point: how and why thinking also should be considered a part of the job. It was a very pertinent piece in today’s times. Beyond schools, even in workplaces, work became synonymous with output and not with the effort/thinking that goes into it.

All these reflect a systemic issue, one that prioritises performance over process, results over reflection. This is corroborated in many research studies that show a significant drop in curiosity as children grow older.

Therefore, building resilience in curiosity becomes just as crucial as sparking it. Struggles, setbacks and not knowing are to be normalised – not feared or avoided. When elders openly admit to not having all the answers and show a willingness to learn, it models intellectual humility, a quality that helps children stay curious even in uncertainty.

A few years ago, a father from a small town made news for hosting a celebration after his son passed his 10th grade. At a time when only top ranks and high scores are typically celebrated, this stood out. Perhaps, for his son – given his academic struggles – merely clearing the exam was a milestone worth honouring. This gesture reinforced that progress deserves as much recognition as perfection.

Creating open-ended challenges will provide scope for children to wrestle with ideas, persist through confusion and experience what is called productive struggle. With ample support at the right times, this builds both confidence and competence.

Journaling – an effective way of expression – can too be a powerful habit. Encouraging children to write not just their answers but also the thinking that led to those answers, allows them to process their own learning and reflect on their reasoning. Over time, this builds metacognition – thinking about one’s thinking – and a deeper self-awareness

Ultimately, when we value thinking over ticking boxes, we foster not just knowledge, but a culture of lifelong learning – where curiosity isn’t something to “grow out of” but something to grow into.