A teacher in a grade 3 classroom asks, ‘What are the colours in a rainbow?’. A student answers VIBGYOR and gets a round of applause from the class. Another student-labelled naughty and distracted in today’s classrooms-raises a different question, ‘How are rainbows formed? The answer he gets is a quick dismissal.

The question here is, why is answering valued more than asking?

The child in question may take weeks or even months to regain the confidence and get themself to ask a question again, whether in public or alone. Curiosity, like children, is delicate and fragile. And yet, it is essential to nurture it with intention and care.

In Part 1, we explored the vital role of curiosity and if the collective society is silencing it, intentionally or otherwise. In part 2, we will explore five simple ways to nurture curiosity, be it at home or school. Exercising these is not an activity in itself, but rather more a way of life that we have long come away from. Because building curiosity is a culture and not something done through sparse episodes.

That curiosity drives learning, memory, and motivation has been well established-both through studies such as those from Gruber’s team and through calls like the NEP 2020 from policy-making bodies. In times when the average attention span is said to be just 12 seconds, it is more important than ever to create an ecosystem that nurtures wonder and sustains curiosity. We are at the peril of entirely losing out a trait as fundamental as curiosity, unless we take active steps to protect and promote it.

The first step in that direction would be to acknowledge and reward questions as much as answers. As we noted in the previous article, most appreciation is reserved for answering right – but rarely for asking right. This sends out a subtle, yet strong message : that answering takes precedence than the questions that lead to them.

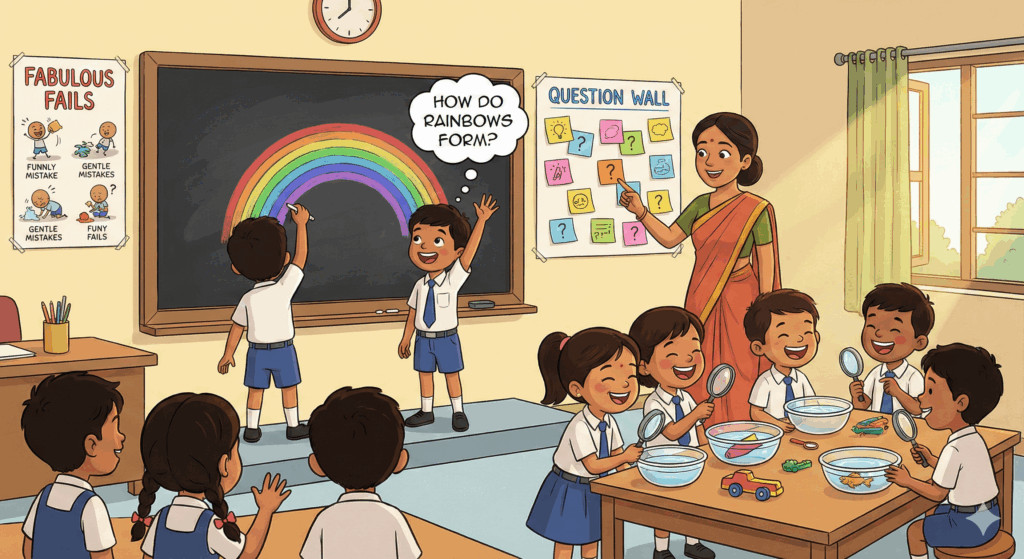

Simple, easy practices like having a ‘Question Wall’ in a classroom – where students put up their questions, however simple or small, can go a long way in normalising inquiry and reinforcing that no question is ‘stupid’.

How many of us have held back ourselves from asking questions – in class or a conference – just for the fear of being judged? With those questions still lingering somewhere in our minds?

At home, complimenting children with, ‘Wow, that’s a good question – I had not thought of that’ not only builds confidence, but also reiterates that curiosity is valued. It will, over time, help them shed inhibitions of being wrong.

The game 20 Questions is a reminder of how fun and interesting questioning can be-and that one can arrive at answers through questioning. Likewise, we have to acclimatise to the fact that sometimes the best answer for a child’s question is another question.

The unhealthy attitude-‘Right now, right here’-is to be challenged with children slowly being nudged to process, think through, and arrive at informed understandings of anything being learnt.

If we were to respond with thoughtful questions rather than rushed answers for what’s asked, we create space for engaging and meaningful conversations. Joining them in exploring answers together would model the idea that adults do not know it all either and that learning is a lifelong pursuit – if one remains curious enough.

Children learn best when they are hands-on and emotionally involved. Encouraging playful exploration and unstructured thinking – through free play or pretend scenarios – are some powerful ways. Spatio-temporal opportunities whether as exploration boxes at school or involving a child in the kitchen at home would offer them no-pressure, unstructured environments where curiosity best thrives.

A concept like buoyancy, for instance, can be understood with things as simple as a bowl of water and a toy – turning everyday moments into learning experiences.

This approach of experiential and play-based learning in the early years and beyond is strongly recommended by NEP 2020.

A wise parent once told his child, ‘Never attach yourself to the results, but focus only on your efforts’. He was, in all probability, taking a timeless lesson out of the Bhagavad Gita. Nevertheless, the message that went home was this – it is okay to make mistakes.

Unfortunately, what often holds back anyone, children or adults the most, is the fear of failure. This fear can intellectually cripple, making it all the more critical to normalise mistakes. Given the innocence of children, validation from elders becomes a powerful reassurance in their pursuits.

Acknowledging and appreciating efforts, for example, by a light-hearted classroom activity like ‘Fabulous Fails of the week’ will reiterate that efforts matter more than perfection.

Carol Dweck, a renowned American psychologist, in her years of work, introduced the concept of fixed and growth mindsets. While the fixed mindset is marked by the belief that one’s abilities are static, the growth mindset fosters belief that abilities can be improved through effort. A growth mindset fuels intrinsic motivation by valuing the process over the outcomes – creating a safe space for curiosity to thrive as children feel encouraged to explore, question, and learn without fear of failure.

Children are like perfect mimics – what they see, they emulate. Be curious yourself – ask questions, explore new ideas and wonder aloud. When children see adults engage in curiosity without fear of being wrong, they will learn that it is okay to not have all the answers – what matters the most is the willingness to ask and learn.

Sharing your own ‘why’ questions with them, and being visibly curious – showing excitement about new information, or even saying “I don’t know, let’s find out together” can model lifelong learning and help them internalise this as a norm.

If we begin to inherently practice even a few of these strategies, we won’t be just nurturing curiosity in children – we will be reshaping the way the next generation thinks, learns and engages with the world.

Once the track is laid and the groove set, how do we sustain curiosity in the long run – especially when challenges arise? In the next and final part of this series, we will explore how to keep curiosity alive through setbacks, build resilience in learners, and nurture deeper, lifelong learning habits.